A Legacy in Gold: A Definitive Glossary of Italian Jewelry Materials and Craftsmanship from Antiquity to the VicenzaOro Exhibition

Introduction: The Golden Thread of Italian Artistry

Italy’s legacy in goldsmithing and jewelry production is a narrative that spans millennia, a continuous thread of artistry and innovation woven through its history. This report serves as a definitive historical and technical glossary, meticulously tracing the evolution of materials and craftsmanship from the Etruscan civilization to the present day. It culminates in an analysis of contemporary innovations and trends showcased at the VicenzaOro exhibition, demonstrating how ancient techniques and enduring traditions form the bedrock for modern experimentation. The central theme of this exploration is the symbiotic relationship between past and future, where Italy’s rich artisanal heritage is not a static relic but a dynamic, living force that continues to define the global standard of “Made in Italy.”

The structure of this report is organized chronologically, with each section serving as a detailed entry in this comprehensive glossary. It begins with the foundational techniques of antiquity, moves through the re-imaginative artistry of the Renaissance and the revivalist movements of the 19th century, and concludes with the technological leaps and aesthetic shifts of the 21st century. This progression highlights how each era built upon the last, transforming jewelry from a sacred, symbolic artifact into a reflection of evolving social values and technological capabilities.

| Historical Period | Primary Materials | Key Workmanship Techniques |

| Etruscan (8th – 3rd Century BCE) | Gold, silver, bronze, lapis lazuli, amber, turquoise. | Granulation (colloidal soldering, fusing), filigree, embossing, chiseling. |

| Roman (1st Century BCE – 5th Century CE) | Gold, silver, bronze, precious and semi-precious stones (garnet, emerald, jasper), colored glass, pearls. | Mass production (molds, casting), gemstone setting, intaglio engraving. |

| Renaissance (14th – 17th Century) | Gold, vermeil, precious stones (diamonds, rubies), enamel, coral, onyx, agate. | Enameling (Cloisonné, Champlevé, Plique-à-jour), repoussé, chasing, cameo, intaglio, filigree, granulation. |

| Baroque (17th – 18th Century) | Gold, silver, diamonds, rubies, emeralds, sapphires, pearls, imitation stones (strass). | Gemstone cutting and setting, filigree, engraving, en ronde bosse. |

| 19th Century Revival | Gold, silver, precious and semi-precious stones (garnet, agate, chalcedony). | Granulation, filigree, miniature mosaics, gemstone setting. |

| Modern Era (20th Century – Present) | Gold, silver, platinum, titanium, aluminum, innovative alloys, lab-grown gems. | 3D printing (powder metallurgy), Buccellati’s Tulle, Florentine finish, lost wax casting, stone setting with microscopes. |

Part I: The Foundations of Italian Craftsmanship: Antiquity

The Etruscan Masters (c. 8th – 3rd Century BCE)

The Etruscan civilization, flourishing in present-day central Italy, laid the groundwork for the country’s unparalleled tradition in jewelry making. Their artistry was not merely ornamental; it was a sophisticated expression of spiritual belief and social status.

Granulation: The “Mystery” of Fused Gold

Granulation, the art of covering a metal surface with tiny spherules of precious metal, was the signature hallmark of Etruscan goldwork. While the technique is thought to have originated in Sumer and spread through Mesopotamia and Greece, it was the Etruscan craftsmen who elevated it to an art form of unmatched complexity and beauty. They achieved a level of virtuosity by meticulously working with gold granules as minuscule as two-tenths of a millimeter, creating intricate designs and textural contrasts on the gold base.

The Etruscans’ mastery was due to their advanced soldering methods. Colloidal soldering utilizes a mixture of tragacanth gum and copper salts to lower the melting points of both the granules and the base metal, causing the copper to diffuse at the point of contact and create a strong, clean bond. Another method,

fusing, joined metals of the same alloy using heat alone, resulting in a bond with no visible solder. The complexity of these processes shrouded their work in mystery, which only added to its fame and allure. The secret was lost for centuries until the 19th-century Castellani family dedicated themselves to its rediscovery.

Filigree: The Art of Delicate Wirework

Parallel to granulation, the Etruscans also perfected filigree, a technique involving the weaving and twisting of fine metal threads into intricate, lace-like patterns. This process allowed for the creation of delicate and lightweight yet structurally complex pieces, such as earrings, necklaces, and brooches. Both filigree and granulation were central to Etruscan artistry, showcasing a level of technical skill that set them apart.

Classical Materials and Symbolism

Gold was the predominant material, viewed by the Etruscans as a sacred metal associated with the sun and believed to possess purifying and healing properties. Silver was also highly valued, symbolically linked to the moon and the goddess Selene.

Unlike later periods that would emphasize faceted stones, the Etruscans integrated gemstones like lapis lazuli, amber, and turquoise for their spiritual and protective qualities. They believed these materials could enhance the wearer’s physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. This perspective highlights a crucial aspect of their jewelry: it was not merely an aesthetic object but a multi-functional artifact imbued with deep symbolic meaning. Pieces were often found in tombs, underscoring their role in funerary rites and the belief that they could accompany the deceased on their journey to the afterlife. This holistic view of jewelry, where artistry and spirituality were intertwined, is a defining feature of the Etruscan tradition.

The Roman Shift (c. 1st Century BCE – 5th Century CE)

As the Roman Empire expanded, a dramatic shift occurred in jewelry design, influenced by new access to materials and a changing social structure.3 Roman jewelry moved away from the intricate metalwork of the Greeks and Etruscans to a style that prioritized colored gemstones and glass.10

New Materials and Techniques: The Rise of Mass Production

The Empire’s vast territorial control and extensive trade routes, particularly the Persian Silk Road, provided an unprecedented abundance of precious and semi-precious materials. Stones like garnets, emeralds, jasper, and lapis lazuli flowed from Egypt, while amber and onyx arrived from the Persian Gulf. This ready availability of resources led to a new aesthetic that valued the “ostentatious and creative use of color” over fine metalwork.

A key technical innovation was the move toward mass-produced jewelry using molds and casting methods. This contrasted sharply with the singular, handmade pieces of earlier civilizations and made adornment more accessible to a broader public, though the wealthy continued to wear pieces made of solid gold and silver. Skilled glass-makers of the era were so adept at their craft that they could create glass beads and ornaments that convincingly imitated genuine gemstones, further democratizing the ownership of visually striking pieces.

The Roman period marks a pivotal turning point in the evolution of jewelry. The shift to mass production and the use of inexpensive materials for the lower classes signals a transformation from a sacred, high-craft item to a more accessible symbol of public status and personal style. Jewelry became a means of signaling one’s position within a complex social hierarchy, with senators and bureaucrats wearing gold rings with flashy gemstones, while plebeians were limited to iron rings. The focus shifted from the spiritual power of the object to its social and visual impact.

Part II: The Rebirth of Artistry: Renaissance to Baroque

Renaissance Rebirth (c. 14th – 17th Century)

The Renaissance marked a golden age for Italian jewelry, with cities like Florence, Venice, and Rome emerging as global hubs of creativity and innovation. Goldsmiths of this era were as revered as the painters and sculptors, and their work was treated as miniature art.

The Jeweler as a Sculptor: Mastery of Metals and Gems

Renaissance jewelry was characterized by intricate gold settings, where the metal itself served as the primary canvas for extensive decoration. Goldsmiths employed a variety of techniques, including casting, chasing, hammering, and soldering. The designs were influenced by the era’s focus on Humanism and a renewed interest in classical antiquity. This led to a departure from medieval religious motifs, with pieces featuring mythological scenes, real-life objects, and naturalistic themes, such as foliage and animals. This period represented a deliberate re-engagement with both ancient artistic ideals and technical mastery.

Enameling: A Palette of Vibrant Color

Enameling was a popular decorative technique for adding vibrant color to jewelry. Three principal techniques were widely used:

Cloisonné, which uses thin metal wires to create compartments for the enamel ;

Champlevé, which involved applying enamel to incisions cut directly into the metal’s surface; and

Plique-à-jour, which filled voids with transparent enamel to create a stunning, stained-glass-like effect. This allowed jewelers to create intricate miniature paintings on pendants, brooches, and rings.

Sculptural Techniques: Repoussé and Chasing

The ancient techniques of repoussé and chasing reached new artistic heights during the Renaissance. Repoussé involved hammering a metal sheet from the reverse side to create a raised, relief design, while chasing added fine details and texture from the front. These techniques allowed artisans to create remarkably detailed, sculptural pieces that showcased their technical prowess.

Gem-Carving: Cameo and Intaglio

Cameo and intaglio were carving techniques applied to semi-precious stones and shells. Cameos involved cutting an image in relief, creating a raised silhouette, while intaglios carved the image deep into the stone. Both were exceptionally popular for creating portraits, mythological scenes, and religious images.

The Renaissance marks a profound artistic evolution in Italian jewelry. While the Roman era had prioritized the gemstone itself, the Renaissance returned the focus to the intricate craftsmanship and design of the gold setting. This fusion of ancient techniques with a new artistic sensibility set the stage for the opulence of the succeeding era.

Baroque Grandeur (c. 17th – 18th Century)

The Baroque period embraced extravagance and opulence, a style that was reflected in its jewelry with intricate designs, lavish materials, and an emphasis on movement and dynamism.

Materials: The Rise of the Diamond and Precious Stones

The availability of precious stones, particularly diamonds, increased significantly due to intensified trade with India. As a result, gemstones like diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires took center stage, their brilliance enhanced by improved cutting and foiling techniques. Jewelers began to use more delicate mountings, designed specifically to highlight and enhance the stone rather than overpower it with goldwork. The elegance of pearls, especially from the Persian Gulf, was also highly fashionable, often worn in sets called

parures.

Aesthetics: The Emphasis on Movement and Light

Baroque designs were known for their elaborate motifs, such as flowers, leaves, and scrolls, and were characterized by flowing lines and elaborate curves. A key aesthetic was the emphasis on movement, with pieces designed to catch and sparkle in the light.

The bow motif, originally a functional ribbon used to secure a jewel, became a popular design element in its own right, often crafted from precious metal and adorned with gems.

The growth of the bourgeoisie during this period created a surge in demand for luxury jewelry. In response, the industry began mass-producing high-quality imitations using materials like “strass” (paste) and glass. This parallels the Roman era’s use of mass production for a wider audience, demonstrating a recurring pattern in Italian jewelry history: economic shifts often drive innovations that make luxury aesthetics more accessible. The Baroque era solidified the aesthetic shift from gold-centric designs to gemstone-centric ones, with the gem becoming the true focal point of the piece.

Part III: The Enduring Legacy: Revivalism and Regional Specialization

The 19th-Century Archaeological Revival

The 19th century saw a powerful resurgence of interest in classical antiquity, driven by archaeological discoveries in Italy. This fascination gave rise to the Archaeological Revival movement, a stylistic trend spearheaded by the Castellani family of jewelers.

The Castellani Legacy: Reclaiming Granulation and Filigree

Inspired by artifacts unearthed from Etruscan tombs, Fortunato Pio Castellani and his sons, Alessandro and Augusto, dedicated decades to reviving long-forgotten techniques. Their greatest contribution was the successful reclamation of Etruscan granulation and filigree. By mastering the meticulous process of fusing minuscule gold granules onto a surface, they created a new fashion trend that paid homage to Italy’s ancient past. The Castellani firm successfully marketed their work to the European aristocracy and wealthy tourists, inspiring a wave of imitators and cementing their legacy as pioneers in the history of jewelry making.

The archaeological revival was more than a stylistic trend; it was a potent act of cultural and political promotion. The Castellani family’s work served as a celebration of Italy’s cultural significance at a time of rising nationalism, challenging the dominance of French and English tastes in the process. By transforming ancient craftsmanship into a fashionable, modern style, they made a powerful statement about Italy’s identity and its enduring artistic heritage.

The Great Italian Jewelry Districts

Today, Italy’s jewelry production is characterized by a network of specialized districts, each a living testament to the preservation and evolution of specific techniques.

| District | Primary Specialization | Historical Roots |

| Valenza | High-end and mid-to-high-end jewelry. | Founded in 1817 by goldsmith Francesco Caramora. |

| Arezzo | Industrial-scale gold production. | Ancient “city of gold” influenced by Hellenistic taste. |

| Naples | Coral, cameos, and quick, custom production. | Borgo Orefici district founded in the 15th century. |

| Campo Ligure / Sardinia | Filigree work. | Campo Ligure declared “National Center of filigree jewelery” in 1884. |

Valenza: The Capital of High-End Production

Valenza, in the Piedmont region, has a history as a goldsmithing hub dating back to 1817. It is now recognized as a global capital for high-end jewelry, distinguished by its unique combination of artisan skills, technological innovation, and aesthetic design. Valenza’s workshops employ advanced techniques like lost wax casting, precision stone setting with microscopes, and intricate hand finishing, allowing for the creation of unique, custom pieces with a focus on meticulous detail.

Arezzo: Industrial and Artisan Excellence

Known as the “city of gold,” Arezzo has been a center for goldsmithing since ancient times and is now home to a modern industrial district with over 1,100 companies. Arezzo’s strength lies in its ability to blend centuries-old artisan techniques with modern, industrial-scale production, allowing it to serve a global market while maintaining its reputation for quality and craftsmanship.

Naples: The Hub for Coral and Cameos

The Borgo Orefici district in Naples, with its history dating back to the 15th century, is renowned for its multi-generational traditions. Naples and the nearby town of Torre del Greco are particularly famous for their specialization in the processing of coral and carved shells. The region is also known for its ability to produce custom, high-end pieces on a remarkably quick timeline, a testament to the concentrated skill of its artisans.

Campo Ligure and Sardinia: The Filigree Capitals

The town of Campo Ligure was designated the “National Center of filigree jewelry” in 1884 due to its high concentration of workshops dedicated to the craft. Similarly, Sardinia has a long tradition of filigree, having collected techniques from other Mediterranean cultures to create its own unique style. The continued existence of these specialized centers demonstrates a key pattern in modern Italian industry: the decentralization of the craft into hubs, each focusing on a specific material or technique. This ensures the preservation of ancient skills while allowing for the development of new specializations.

Traditional Workmanship in the Modern Era

Beyond the specialized districts, several traditional Italian techniques continue to thrive and are highly valued today.

Florentine Finish: The Art of Surface Engraving

The Florentine finish is a specialized engraving technique that creates a cross-hatched pattern on the surface of a precious metal. This hand-applied process reduces the metal’s reflectiveness, producing a distinctively matte, textured surface.25 The technique is a closely guarded tradition passed down through generations and remains largely exclusive to traditional Italian workshops.

Murano Glass: The Enduring Craft of Millefiori and Sommerso

Murano glass jewelry, crafted using ancient lampwork techniques, maintains a direct connection to Italy’s artisanal past.

The Millefiori (“thousand flowers”) technique involves creating mosaic patterns from fused glass rods, or murrine, that are then embedded into a molten glass form.

The Sommerso (“submerged”) technique creates striking layers of color by dipping a core of colored glass into different colored layers. Other techniques include Fenicio (feathered glass) and the incorporation of gold and silver foil to add a brilliant sheen.

Chain-Making: The Venetian and Figaro Link

Italian chain-making traditions can be traced back to the Etruscans.

The Renaissance gave birth to the iconic Venetian box chain (catena manin), a flexible and strong design with a square, closely linked pattern that reflected the refined geometry of the era’s architecture.

The 18th century saw the emergence of the Figaro chain, a design characterized by its rhythmic pattern of two or three shorter links followed by one longer one, a style that quickly became a global staple. These enduring styles blend ancient techniques with timeless design, cementing Italy’s reputation as a global leader in the craft.

Part IV: The VicenzaOro Exhibition: Crafting the Future

The VicenzaOro exhibition serves as a dynamic “bridge between past and future,” showcasing how Italy’s millennia-old traditions are used as a foundation for radical innovation. It is a hub for trend forecasting and a platform for designers and manufacturers to experiment with new materials and technologies.

New Materials for a New Age

The exhibition highlights a significant shift towards noble and innovative metals in high-end jewelry. Titanium and aluminum are prominent, used for their ultra-lightweight and resilient properties.

Designers are using these materials to create bold contrasts with diamonds, sapphires, rubies, and pearls, often engraving and anodizing the titanium in a range of colors. This blend of traditional gold and modern materials represents a key approach to contemporary design, where luxury is defined not only by preciousness but also by innovation and unique visual impact.

The industry is also exploring new alloys and embracing lab-grown gemstones to address consumer demand for sustainability and traceability. This aligns with a growing industry focus on reducing environmental impact and promoting ethical practices.

The New Workmanship and Trends

Traditional Italian craftsmanship is now being fused with cutting-edge technology to achieve results previously considered impossible.

3D Printing: Powder Metallurgy and Ultra-Light Architectures

Modern designers are utilizing advanced machinery, particularly 3D printing, to create intricate and unique pieces.

A key technique is powder metallurgy, where precious metals are reduced to a fine powder and used in 3D printers to create “ultra-light architectures”. This innovation allows for complex, lattice-like designs and structural forms that are impossible to achieve with traditional methods like lost wax casting, while still maintaining the inherent value of the precious metal.

Buccellati’s Tulle: A Modern Interpretation of Openwork

The Buccellati brand’s signature Tulle technique, also known as “honeycombing,” is a stunning example of how modern brands are reinterpreting ancient forms. It is a highly labor-intensive process that involves meticulously piercing a sheet of metal with a hacksaw to create a network of tiny polygonal holes. This openwork technique, inspired by Venetian lace, requires immense skill and precision, demonstrating a commitment to traditional hand craftsmanship even within the context of modern design.

Trendvision Forecasts

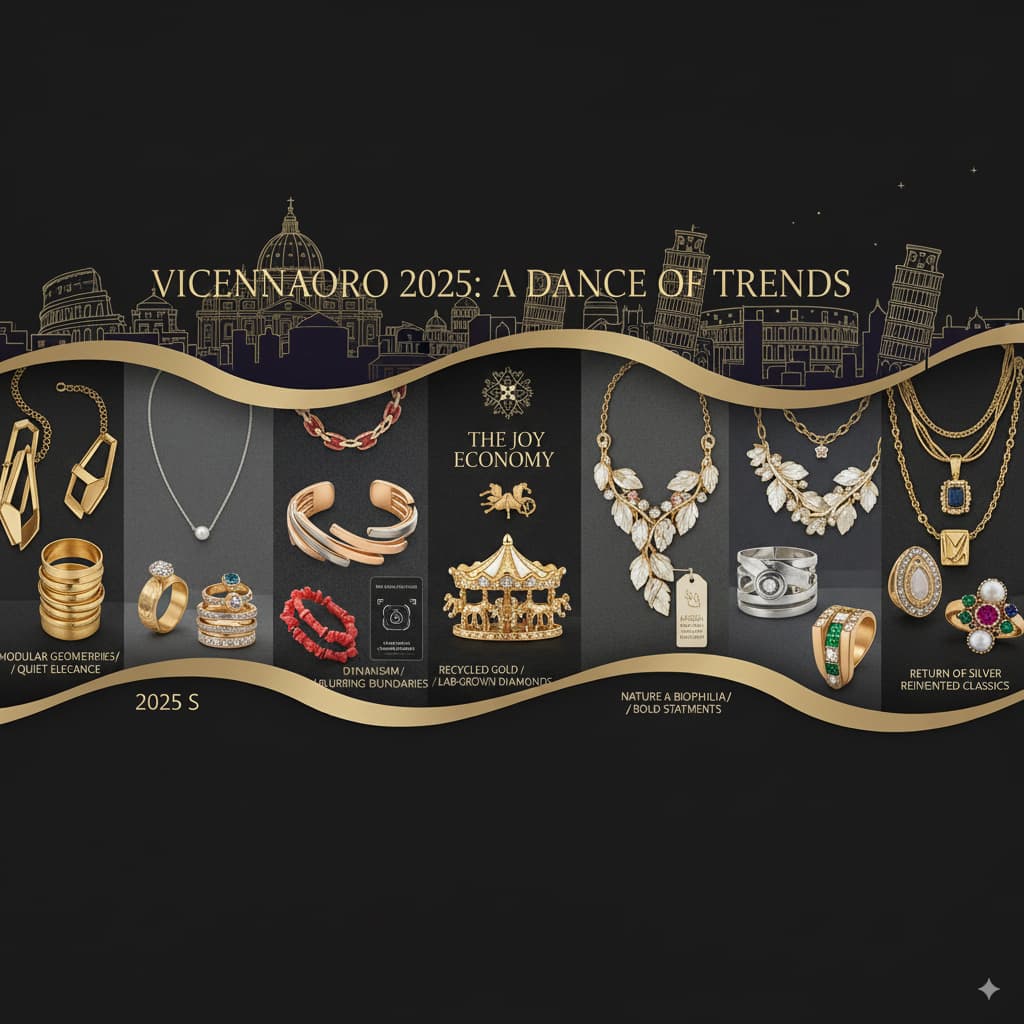

VicenzaOro is a key platform for trend forecasting, led by Paola De Luca of Trendvision Jewellery + Forecasting.

The upcoming season’s forecasts reflect a deep connection between jewelry and evolving cultural values. The trends include:

- Modular Geometries: This trend focuses on jewelry as a customizable system of stackable and interchangeable elements, such as detachable links and reconfigurable clasps.

- Spectrum Play: A playful use of vibrant colored gemstones and enamel, seen in pieces like beaded necklaces and mismatched earrings.

- Quiet Elegance: A minimalist approach that favors soft textures and sustainable materials like satin gold and matte platinum.

- Dynamism: Designs that incorporate movement and fluid silhouettes, inspired by Futurism and Art Deco.

These trends reflect a profound shift in consumer values. The emphasis on “Quiet Elegance” points to a growing desire for ethical, subtle luxury. Meanwhile, the focus on “Modular Geometries” and “Dynamism” demonstrates that jewelry is no longer a static ornament but a customizable, emotional language—a dynamic expression of personal identity and evolution.

Conclusion

The evolution of Italian jewelry is a testament to the enduring power of craftsmanship, a narrative that begins with the Etruscans’ mystical mastery of granulation and continues to unfold with the technological innovations and artistic experimentation of the 21st century. What defines the “Made in Italy” legacy is not simply the raw material but the unparalleled genius in its refinement and application. From the Etruscans who perfected the art of fusing gold to the Renaissance jewelers who elevated their craft to sculpture, and to the 19th-century revivalists who reclaimed lost techniques, Italy has consistently demonstrated a unique ability to bridge tradition with forward-thinking design.

Today, this legacy is embodied in specialized regional districts that preserve ancient skills and in major exhibitions like VicenzaOro, which showcases how traditional craftsmanship can be fused with groundbreaking technologies like 3D printing and powder metallurgy. The industry’s adoption of innovative materials such as titanium and its focus on sustainability further prove its responsiveness to contemporary social and cultural shifts. In the end, Italian jewelry is not just an object of beauty; it is a wearable history, a cultural artifact, and a dynamic reflection of a people who have always understood that true elegance is a timeless dialogue between the hands of the artisan and the spirit of the age.

Below a glossary of classical and contemporary materials and workmanship in Italian jewelry, from ancient traditions to the latest trends showcased at Vicenzaoro.

A Glossary of Italian Jewelry: From Etruscan Gold to Modern Innovation

Italian jewelry is a story of artistry and innovation, a tradition stretching back thousands of years. From the intricate goldwork of the Etruscans to the high-tech materials seen at the Vicenzaoro exhibition, the “Made in Italy” label signifies a legacy of unparalleled craftsmanship. This glossary explores the materials and techniques, both classic and contemporary, that define this rich heritage.

Classical Materials: The Foundations of a Legacy

- Gold (Oro): The cornerstone of Italian jewelry, gold is traditionally used in its rich, warm 18-karat form. Italian goldsmiths are masters of creating various alloys, resulting in the classic yellow gold, as well as elegant white and romantic rose gold.

- Silver (Argento): With a history as old as gold, silver has been used for everything from intricate filigree to bold, modern designs. Sterling silver (925) is the standard for quality.

- Coral (Corallo): The fiery red coral from the Mediterranean, particularly from Torre del Greco near Naples, is an iconic material in Italian jewelry. It is often hand-carved into intricate beads, charms, and cameos.

- Pearls (Perle): A symbol of elegance since the Renaissance, pearls are a staple in Italian jewelry, used in everything from classic strands to contemporary designs.

- Cameos (Cammei): This ancient art form involves carving a relief image, typically a portrait, onto a shell or stone. The area around Torre del Greco is world-renowned for its hand-carved cameos.

- Venetian Glass (Vetro di Murano): For centuries, the island of Murano in Venice has produced exquisite glass, which is often used to create colorful and unique beads for necklaces and bracelets.

- Gemstones (Pietre Preziose): Italy has a long history of incorporating precious and semi-precious stones into its jewelry. From the vibrant colors of rubies, emeralds, and sapphires to the unique beauty of turquoise and lapis lazuli, gemstones are central to Italian design.

Classical Workmanship: The Art of the Italian Hand

- Granulation (Granulazione): An ancient technique perfected by the Etruscans, granulation involves applying tiny gold spheres to a surface to create intricate, textured patterns. This highly skilled process is still used today in artisanal jewelry.

- Filigree (Filigrana): This delicate art form involves twisting fine threads of gold or silver and soldering them together to create lace-like designs. It is a hallmark of traditional Italian jewelry.

- Repoussé and Chasing (Sbalzo e Cesello): A metalworking technique where a design is hammered from the reverse side to create a relief (repoussé) and then refined from the front with specialized tools (chasing).

- Micro-mosaic (Micromosaico): A technique that originated in Rome, micro-mosaics are intricate pictures created from tiny, colored glass tiles (tesserae). These were popular in Grand Tour jewelry of the 18th and 19th centuries.

- Engraving (Incisione): The art of carving a design into a metal surface is a fundamental skill in Italian jewelry making, used to add detail, texture, and personalization to a piece.

New Materials & Techniques: The Future Forged at Vicenzaoro

The Vicenzaoro fair is a window into the future of jewelry, showcasing how Italian designers are embracing new materials and technologies to push the boundaries of their craft.

- Titanium (Titanio): Valued for its strength, lightness, and ability to be anodized in a rainbow of colors, titanium is being used to create bold, contemporary, and surprisingly lightweight pieces.

- Carbon Fiber (Fibra di Carbonio): Known for its durability and modern aesthetic, carbon fiber is often incorporated into men’s jewelry and avant-garde designs, frequently paired with gold and diamonds.

- Recycled and Sustainable Materials: In response to growing consumer demand for ethical luxury, Italian brands are increasingly using recycled gold and other metals. The emphasis is on creating a circular economy within the jewelry industry.

- Lab-Grown Diamonds (Diamanti Sintetici): Lab-grown diamonds are gaining traction as a sustainable and ethical alternative to mined diamonds. They are chemically and physically identical to natural diamonds and are being featured in a growing number of high-end Italian collections.

- Advanced Technologies: Italian jewelers are innovators, adopting technologies like 3D printing to create complex and intricate designs that would be impossible to achieve by hand, and laser cutting for precision and detail.

This blend of ancient tradition and modern innovation is what makes Italian jewelry a constantly evolving art form, cherished around the world for its beauty, quality, and timeless appeal.